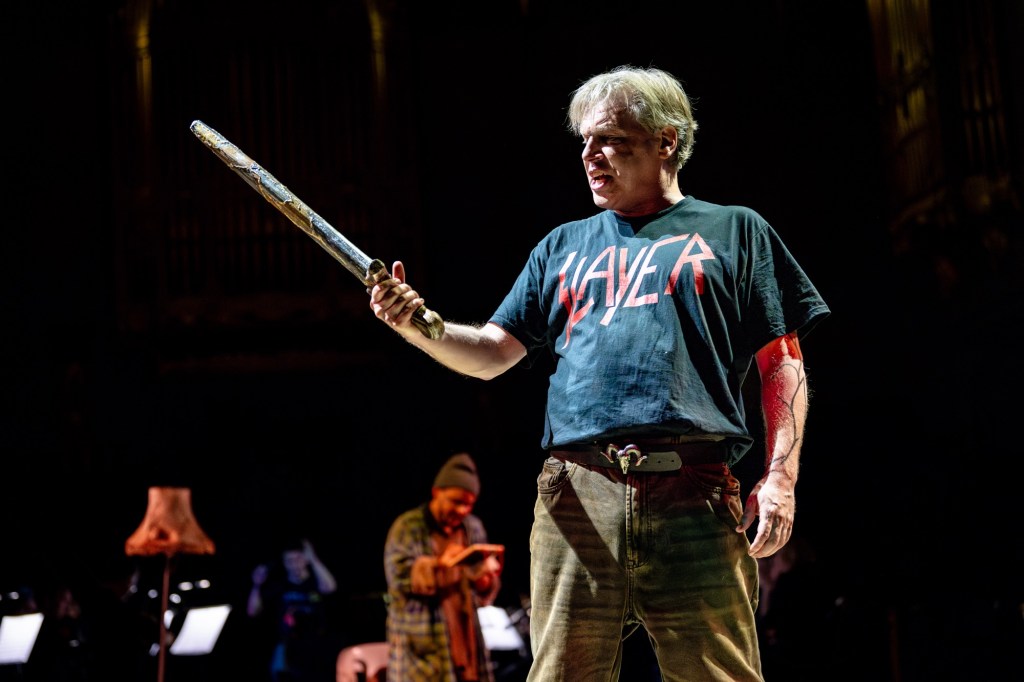

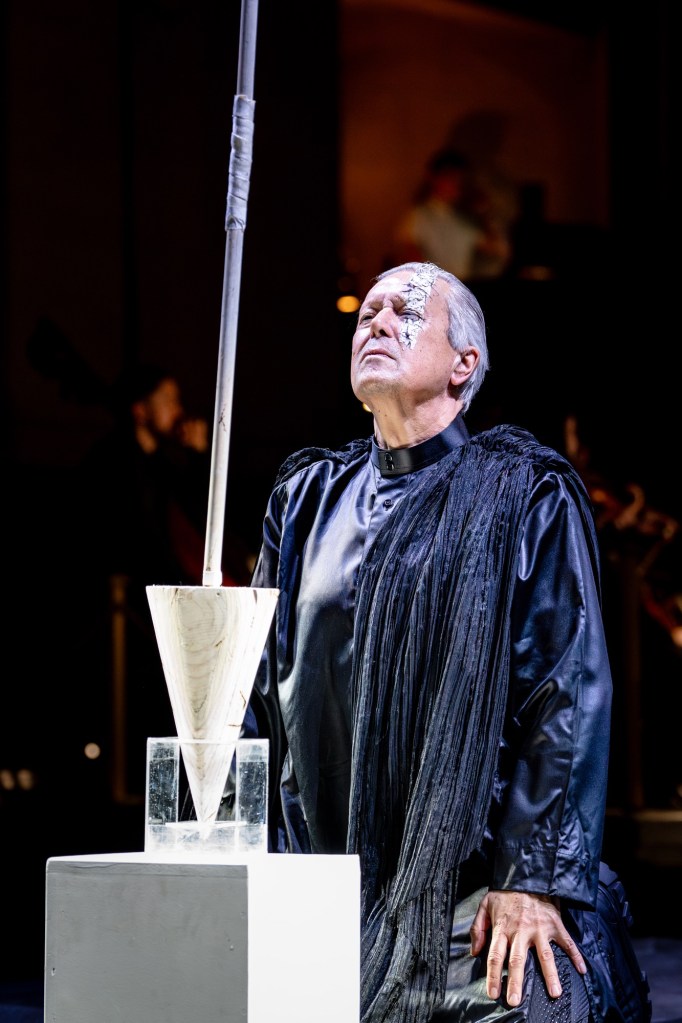

Siegfried and Mime in a ‘cave in the rocks’ is visited by the Wanderer with a prophecy, Production photos by Steve Gregson

Set and Costume Design for Opera | Regents Opera, Freemasons Hall

Directed by Caroline Staunton

Written by Richard Wagner

Lighting Design by Patrick Malmström

Arrangement & Musical Direction by Benjamin Woodward

Production Management by Adam Smith

Produced by Sarah Heenan & Adam Smith for Regents Opera

Costume Supervision by Cieranne Kennedy-Bell

HMUA by Tabitha Mei Bo-Li

Scenic Art by Jemima Rose

Cast: Peter Furlong, Ralf Lukas, Oliver Gibbs, Holden Madagame, Catharine Woodward, Corinne Hart, Craig Lemont Walters, Mae Heydorn

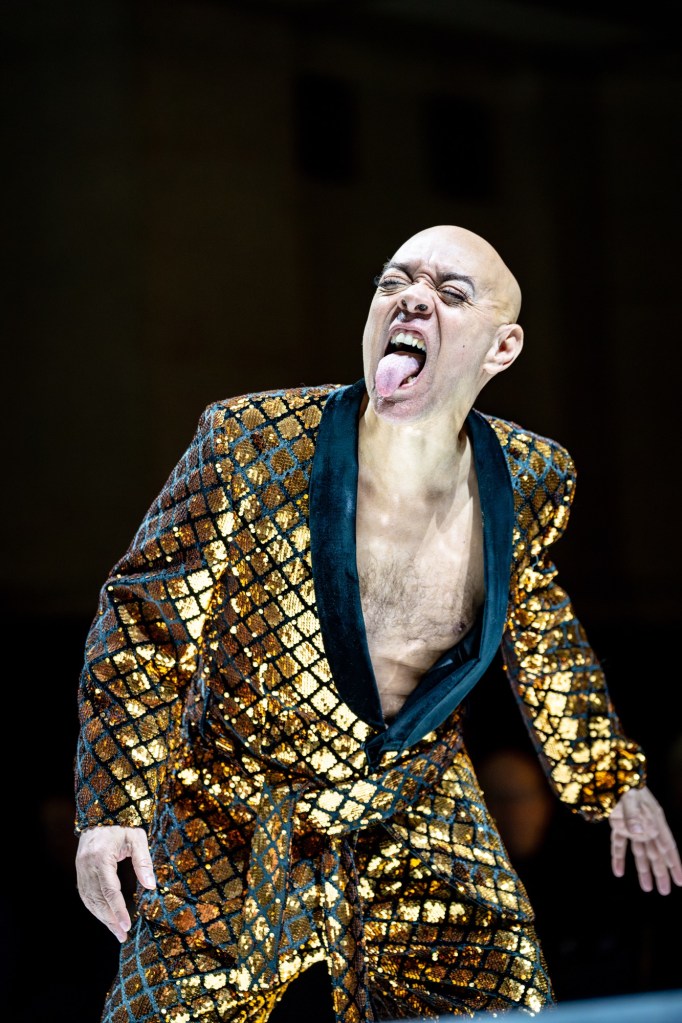

Fafner’s Lair, Production photos by Steve Gregson

Siegfried, the third opera of Regents Opera’s Ring Cycle follows the story of Siegfried, Wotan’s Demi-god secret grandson & the realisation this means the prophecy that he would kill his grandfather will come true.

The decay of the world continues. We begin however in part of the world that Wotan’s power never touches. A dark corner of the world held hostage by the fearsome dragon Fafner. Here Niebelung Mime brings up young and reckless Siegfried whom he both mistreats and fears in equal measure. This environment had to give both the sense of a gritty domestic environment, with links to the metal forging they both do. Their home is dank and disgusting but Mime still maintains a pride in his own corner of it, welcoming a mysterious electrician (Wotan in disguise as The Wanderer) to fix his flickering light.

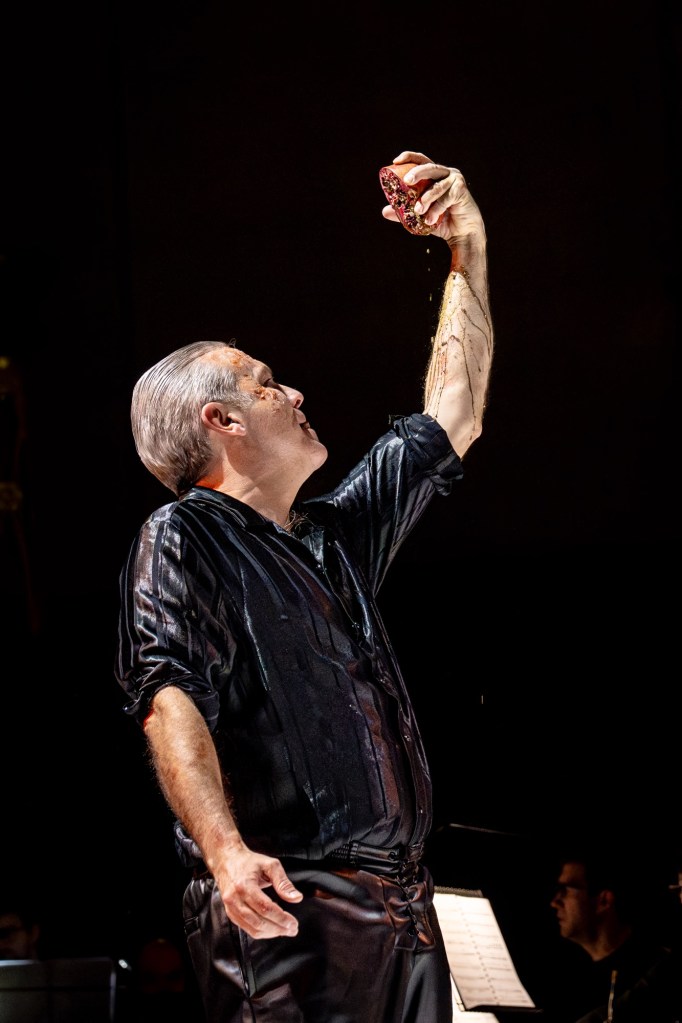

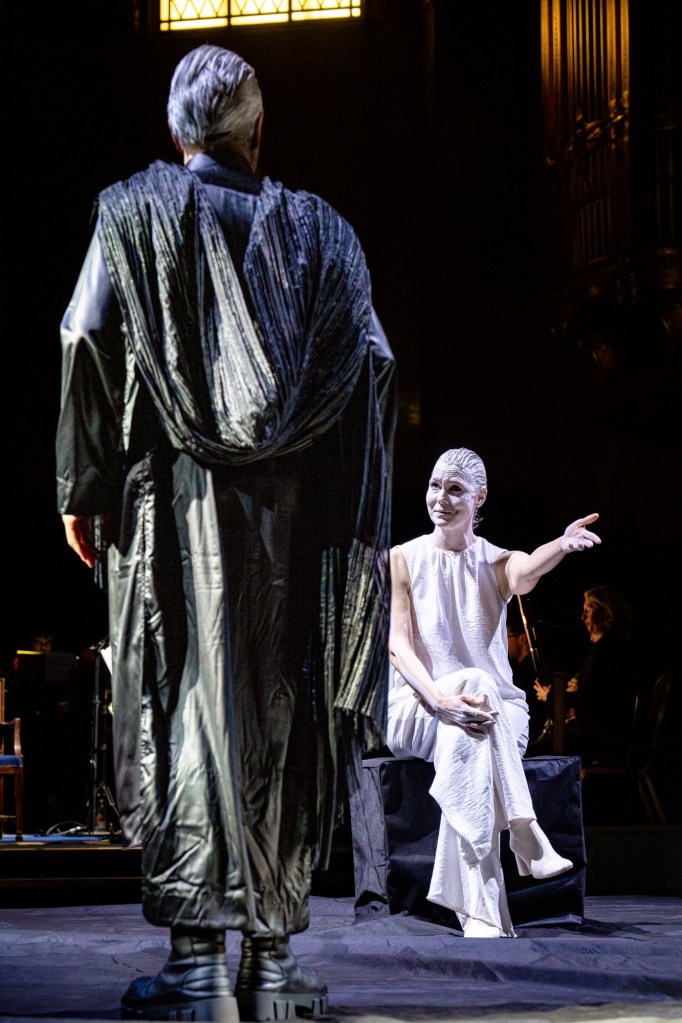

Wotan & Erda, Siegfried & Brunnhilde fall in love, Production photos by Steve Gregson

The second act takes Siegfried on a quest to kill the dragon Fafner. Here we continue the theme of art. Welcomed to a gallery’s opening, audience’s hands stamped on entry by the Waldvogel. Fafner portrays himself as a high camp, bejewelled piece of art in a gallery of flickering videos of decay. The space is a clinical white, highlighting what a different world scruffy Siegfried enters. Fafner’s power here is psychological, he plays and taunts Siegfried, dressing as Sieglinde. The Wanderer & Alberich watch from afar. The Wanderer here acts as a slightly slicker mirror to Alberich. Alberich’s skin burnt from the curse of the gold, leaves liquid scars, both men wear inky blacks, dressed up to enter the gallery.

Once Siegfried manages to kill Fafner, his innocence has stripped from him. We touch here in his mental instability in the form of a strange, fever-dream musical dance number. Brothers Alberich & Mime in top hats and tails dance and taunt him; Mime, fearing of Siegfried entices him with a poisonous drink. In a moment of lucidity Siegfried hurdlers his adoptive father Mime in a bid to take control of his life.

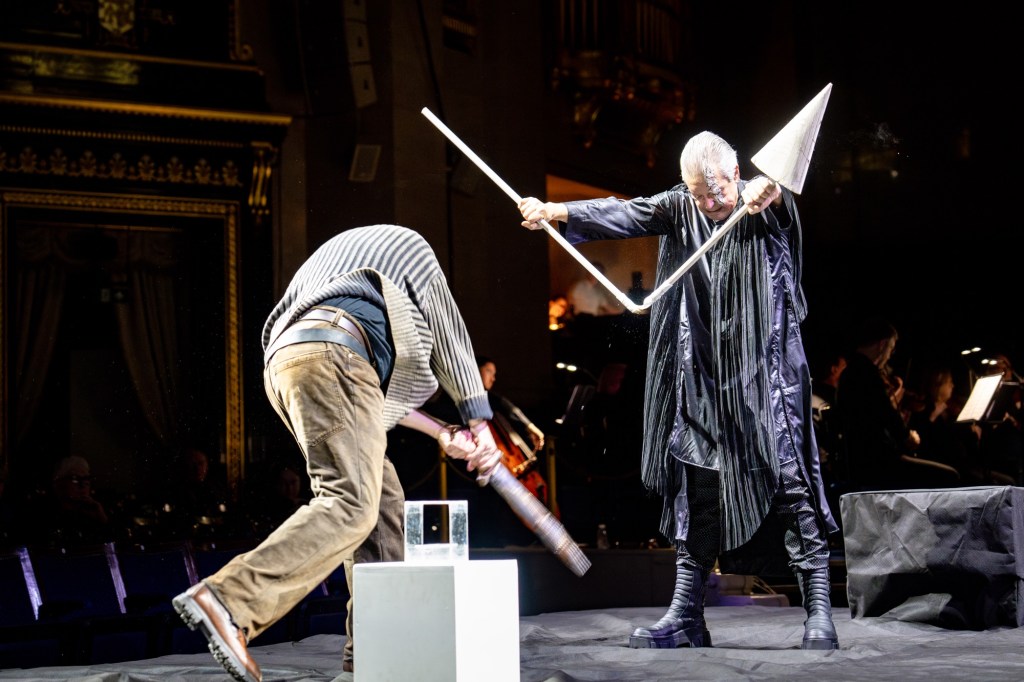

Wotan, called back in his true form to Walhalla by the mysterious Erda. The space is sunk into darkness, only her purity and continuity shine through. Siegfried manages to follow Wotan, and revealed in his true identity they fight, sword against infallible spear. The broken Wotan must therefore allow Siegfried his prize.

the world transforms from black to a gentle, heavenly, feather-filled white. The Waldvogel feathers the love nest for Siegfried & Brunnhilde’s young romance.

“wonderful moments when Siegfried forged his sword on a toilet before slashing the bog in twain with a clean sweep. His adoptive father Mime and pseudo-uncle Alberich treated us to a top hat and cane dance while waiting for a dragon to die.”

Andrew Lohmann, London Unattached

“Caroline Staunton’s staging enhances Siegfried’s dramatic power. […] Art runs through Staunton’s Ring, from the exhibition space of Rheingold through the parade of classic paintings (the departed) in Walkure. In Siegfried’s second act, video monitors flicker into arty life and back to static again; the Woodbird, in an expanded if silent role, is the gallery’s host. A box, installation art, at one end of the stage is ‘Fafner’s lair’. Perhaps the greatest surprise is the scene between Alberich and Wanderer, rendered as vaudeville (to fine effect, as if Staunton’s staging is itself mocking the idea of Siegfried as scherzo, as ‘joke’). In the final act, a white space represents infinite possibility, manifest in the freedom of the Woodbird herself; a clear turning point enabling new paths forward.”

Colin Clarke, Opera Now

“Continuing ‘the theme of the self as both subject and objet d’art’, Act II takes place in The Woodbird’s curated art space, courtesy of designer Isabella van Braeckel. If on paper the idea sounds slightly pretentious, in the event it works very well. As television screens revealing art videos line both sides of the stage, The Woodbird shows Alberich and then other characters into the gallery, offering them drinks and nibbles. Alberich’s encounter with Wotan consequently seems to take place at a private viewing, with the similar hairstyles and stylish clothes they sport highlighting how the two are really cut from the same cloth. In fact, of the pair Wotan’s clothes are the more lavish and this suggests that, if we see Wotan in Das Rheingold as a Bourgeois figure, he is now parodying what he once was as he accepts the new world order.”

“Every character sports a different costume in each act, which helps to highlight the transformational journeys that Siegfried and Wotan undergo across the three. White has been used throughout this Cycle as a symbol of purity, with the fact that Wotan’s patch is represented by a white smear across the relevant side of his face suggesting that he surrendered his purity when he lost his eye. Conversely, Erda appears totally in white revealing how she has not gone astray like the other gods. […] White is also the dominant colour on the rock as a series of transparent hanging ‘net curtains’ grace the stage. The final scene proves to be a revelation”

Sam Smith, Music OMH

“One of the exhibits in the Woodbird’s gallery is a large box in which Fafner could be dimly seen, coiling mysteriously, through the angry encounter between Ralf Lukas’s commanding Wanderer and Oliver Gibbs’s tetchy and pugnacious Alberich. The emergence of the dragon – dressed in a suit of gold scales, and with a suitably cavernous voice – is mesmerising, the movements of his head and body (and tongue) eerily ophidian.”

Chris Kettle, Scene and Heard International